James Frazer has a lot to answer for.

He was born in 1854 in Glasgow, Scotland. He became a Fellow of Classics at Trinity College, Cambridge. From there he leapfrogged sideways into folklore studies and comparative anthropology, two disciplines he knew nothing about (although to be fair, at the time, neither did anyone else really.) His masterwork was The Golden Bough, two volumes of meticulously researched albeit fairly wrong comparative mythology from all over the world. His research was conducted mostly by postal questionnaire since he wasn’t into travelling. The title of the book comes from one of the more mysterious bits of the Aeneid , where the Roman epic hero finds a magical golden branch which he then has to hand over to a priestess in exchange for passage to visit the land of the dead.

Frazer had some Complex Views About Religion. He basically decided that cultures moved through stages—starting with ‘primitive magic’, and then moving to organised religion, and finally arriving at science. How did he know what primitive magic was like? Well, he studied the beliefs of primitive peoples (by postal questionnaire, remember). How did he know they were primitive? Well, he was a Fellow of Classics at Trinity College and this was during the height of the British Empire, so practically everyone who wasn’t him was primitive. Convenient!

I’m not going to go into real depth here (like Frazer, I’m a classicist talking about stuff I don’t know that well; unlike Frazer, I’m not going to pretend to be an expert) but what you really need to know is people ate it up . Magic! Religion! Science! Sweeping statements about the development of human belief! Universal theories about What People Are Like! All wrapped up in lots of fascinating mythology. And he treated Christianity like it was just another belief system , which was pretty exciting and scandalous of him at the time. Freud mined his work for ideas; so did Jung—the birth of psychology as a discipline owes something to Frazer. T.S. Eliot’s most famous poems were influenced by The Golden Bough. It was a big deal.

But the main thing that is noticeable about the early-twentieth-century attitude to folklore, the post-Golden Bough attitude to folklore, is: it turns out you can just say stuff, and everyone will be into it as long as it sounds cool .

(Pause to add: I am not talking about the current state of the discipline, which is very much Serious and Worthy of Respect and therefore Not Hilarious, but about the joyous nonsense interspersed with serious scholarship which is where all the children’s folklore books my grandma had got their ideas.)

Take the Green Man.

Where does the Green Man mythos come from?

I’m so glad you asked. It comes from Lady Raglan’s article The Green Man in Church Architecture in the 1939 edition of “Folklore”, making this timeless figure out of pagan memory exactly eighty years old this year.

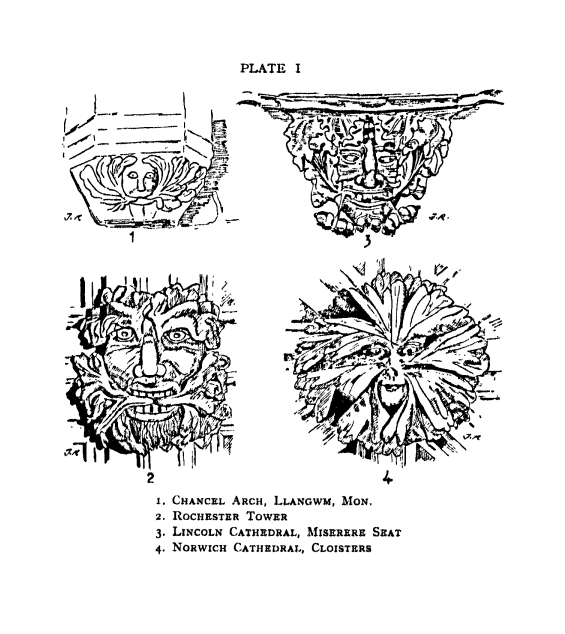

Lady Raglan made precisely one contribution to the field of folklore studies and this was it. She noticed a carving of a face formed out of entwined leaves in a church in Monmouthshire, and then found other examples in other churches all over England and Wales. She named the figure ‘the Green Man’. (Before that this motif in ecclesiastical decoration was usually called a foliate head, because it’s a head and it’s made out of foliage.) She identified different types of leaves—oak! That’s ‘significant’ according to Lady Raglan. Poison ivy! ‘Always a sacred herb.’

So: a human face made out of leaves, appearing in church after church. Could the sculptors have made it up because carving leaves is fun? Absolutely not, says Lady Raglan:

‘…the mediaeval sculptor [n]ever invented anything. He copied what he saw…

This figure, I am convinced, is neither a figment of the imagination nor a symbol, but is taken from real life, and the question is whether there was any figure in real life from which it could have been taken.’

You heard it here first: it is literally impossible for artists to imagine things.

Lady Raglan’s conclusion:

The answer, I think, is that there is only one of sufficient importance, the figure variously known as the Green Man, Jack-in-the-Green, Robin Hood, the King of May, and the Garland…

Again I am not going to go into depth, so here’s the short version: this is kind of nonsense. There are like four separate traditions she’s conflating there. (To pick just one example: she’s talking about eleventh-century carvings, and Jack-in-the-Green—a traditional element of English May Day celebrations involving an extremely drunk person dressed up as a tree—is eighteenth-century at the earliest.)

The essential thesis of the Green Man myth is that the foliate head carvings you can find all over western Europe represent a survival . They are, supposedly, a remnant of ancient pre-Christian folklore and religion, hidden in plain sight, carved into the very fabric of the Christian churches that superseded the old ways. The Green Man is a nature spirit, a fertility god, a symbol of the great forests that once covered the land. He’s the wilderness. He’s the ancient and the strange. He’s what we’ve lost.

And here’s the Golden Bough of it all: this might be, historically speaking, dubious, but you can’t deny it sounds cool.

And you know what? It is cool.

Buy the Book

Silver in the Wood

As a folklorist, Lady Raglan’s historical research skills could have used some work. But as a myth-maker, a lover of stories, a fantasist , she was a genius and I will defend her against all comers. There is a reason the Green Man starts cropping up in twentieth-century fantasy almost at once. Tolkien liked it so much he used it twice—Tom Bombadil and Treebeard are both Green Man figures.

Lady Raglan might or might not have been right about pagan figures carved into churches. It is true that there are foliate heads in pre-Christian traditions; there’s Roman mosaics that show a leaf-crowned Bacchus, god of fertility and wildness. It is true that there are several European folk traditions of wild men, ‘hairy men’, people who belong to the uncultivated wilderness. But foliate heads are only one of several Weird Things Carved Into Churches, and no one has proposed that the grotesques and gargoyles (contemporaneous, show up in the Norman churches where foliate heads are most common, pretty weird-looking) are actually the remnants of pagan deities. Mermaid and siren carvings have not been assumed to represent a secret sea goddess. The pagan-deity hypothesis has been put forward about the Sheela na Gig, little female figures exposing their vulvas posted above the doors of—again—Norman churches, especially in Ireland. (What is it with the Normans?) But there are other explanations for all of these. Are they ugly figures to scare off demons? Abstract representations of concepts from Christian theology? Could it even be that Sometimes Artists Make Stuff Up?

Do we know?

No, we don’t.

And I’m not sure it matters.

The Green Man mythos—eighty years old this year, in its modern form, its syncretic form that pulls together half a dozen scattered and separate strands of folklore, many of them also dubiously historical—doesn’t have to be Real Authentic Definitely Pre-Christian Folklore to be a good concept, a good story, a good myth. Maybe it’s not a coincidence that our Green Man was born in 1939, on the eve of the Second World War. As Europe hurtled for the second time towards the nightmarish meat-grinder of industrialised warfare, it’s not surprising that Lady Raglan’s discovery—Lady Raglan’s creation—struck a chord.

Early folklorists—many of whom seem to have been basically just frustrated fantasy authors—were right about this: you can just say stuff, and everyone will be into it as long as it sounds cool. Which is to say, as long as it sounds right , and meaningful , and important : because a myth is a story that rings with echoes like the peal of a church bell. And by that metric the Green Man is as authentic as any myth as can be. The story almost tells itself. It says: he’s still here. The spirit of ancient woodlands, the enormous quiet of a different, wilder, less terrible world. You can see him lurking in the church; you might glimpse him striding through the forest. He is strange and strong and leaf-crowned. The fearsome forces of civilisation might try to bury him, but his roots are deep, and he will not die.

He is a mystery, but he has not left us yet.

Photo: Simon Garbutt (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Emily Tesh grew up in London and studied Classics at Trinity College, Cambridge, followed by a Master’s degree in Humanities at the University of Chicago. She now lives in Hertfordshire, where she passes her time teaching Latin and Ancient Greek to schoolchildren who have done nothing to deserve it. She has a husband and a cat. Neither of them knows any Latin yet, but it is not for lack of trying. Tesh is the author of Silver in the Wood.